"The whole ceremony was very *you*” Part 2 : Secrets of Synchronicity

Why did the second act include a Louis Vuitton ad, and so many French 1980s references? Why did it almost *not* happen due to a dancers' strike? Also, who just did the best cameo ever on Notre-Dame?

The first act of the opening ceremony, “Enchanté”, was a way to make the international audience lower their guard: “Here is an avalanche of comfy clichés about France. Paris is all about joie de vivre and la vie en rose, even American stars love it here! OK, now that you’re enchanted, let’s introduce you to the real French people”. Regular people, not pop icons, historical figures or video game characters”. The transition had to be as smooth as the Torchbearer ziplining across the Seine (in this scene, my money’s on him being played by urban explorer and Ninja Warrior athlete Clément Dumais [Edit: I was later proved wrong]). Effectively, the Torchbearer was also crossing the Rubicon: there would be no turning back to “Paris as usual”. However, to avoid instantly shocking viewers, the creative team couldn’t suddenly introduce a guillotine: IOC boss Thomas Bach explicitly said there should be no guillotine in the show. No “Workers’ Internationale” proletarian tableau either: both factories and their workers have been priced out of Paris for half a century, so it wouldn’t have been real, current Paris. Instead, the camera turned to Notre-Dame, being rebuilt since the horrendous 2019 fire. At the time, whether Christian or not, people from around the world came together to comfort Parisians, and pitched in to fund the renovations. This “coming together” notion is what, to me, drove the second act: “Synchronicité”.

Synchronicité

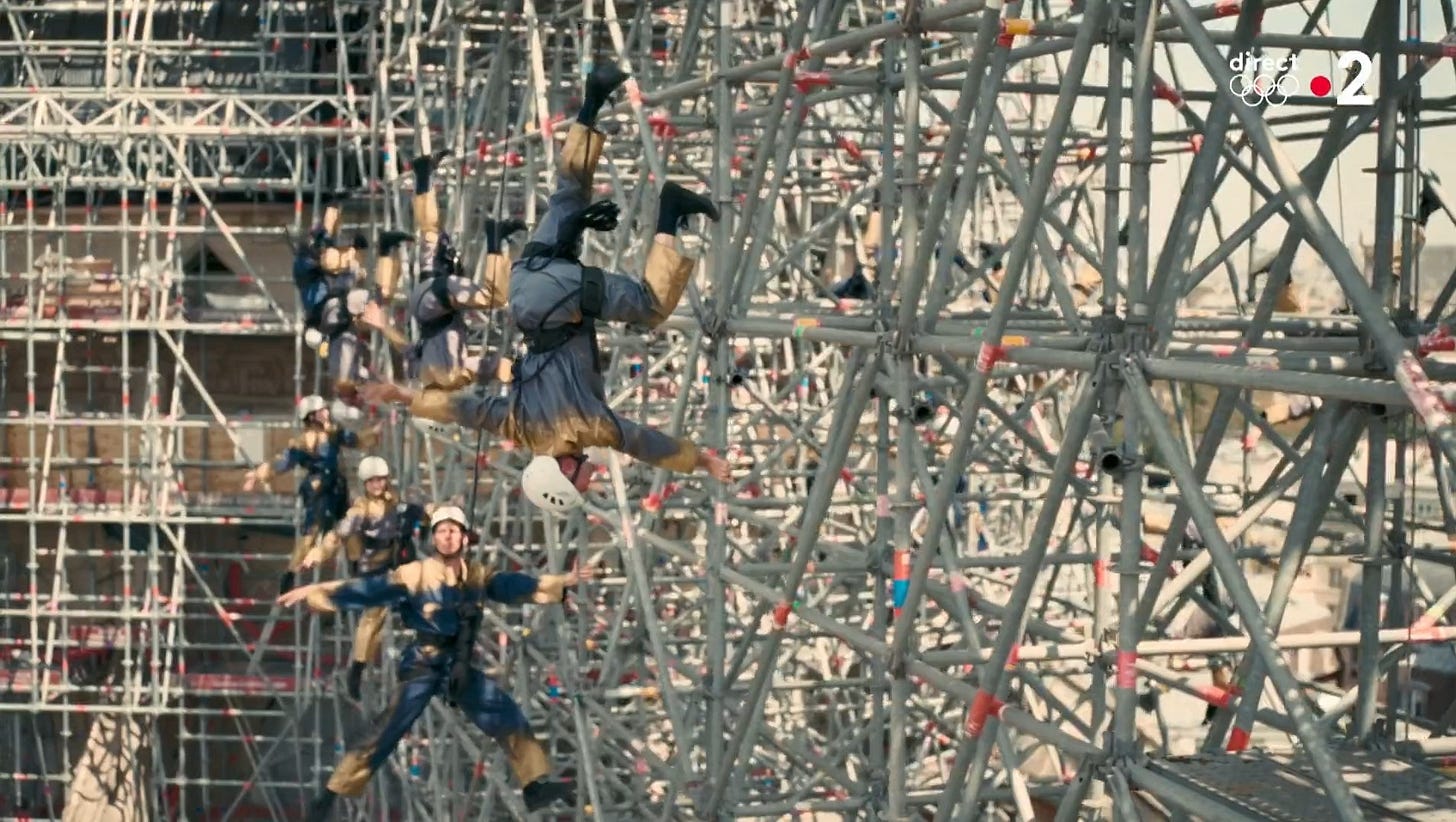

Forget the pseudoscientific Jungian concept of synchronicity, this part is literally about people actively doing things together, in synch. It’s an homage to teamwork: first the craftspeople repairing Notre-Dame –carpenters, stonemasons, roofers, etc– then largest group of dancers of the entire ceremony, choreographed by Maud Le Pladec. In the prerecorded aerial segment, craftspeople are played by one of my favourite dance groups, Compagnie Retouramont, who specialize in vertical dance performances in unlikely places.

The music created using the sounds of tools on wood and stone is probably an homage to Pierre Schaeffer’s “musique concrète”, another Parisian invention that later influenced contemporary composers, from electronica to hip-hop samplers. The slow motion shots, chains and hard hats reminded me of a 1980s ad for the Manpower temp agency. Granted, this 2024 version is much less macho, way more gender-balanced and prioritizes precise manual skills over muscles. But in the end, it’s still about “when we work together we can create wonders”.

The dancers in the puddle (they did rehearse in a artificial pool, but were probably not expecting it to overflow with rain), represented French youth. They were too young to have mastered the tools of the trade yet, but they danced passionately, as one, in their second-hand streetwear (throughout the ceremony, each outfit was unique). You may have noticed that both the workers’ overalls and the dancers’ street clothes were gilded. It sure made them more visually striking and matching the golden background, but it was also to communicate that they are the true golden treasure of France. Today’s France doesn’t have much in the way of natural resources like oil or gold, so it relies on people’s skills and creativity.

The way the Torchbearer jumped from dormer window to dormer window confirmed I was probably looking at one my favourite traceurs, Simon Nogueira, from the French Freerun family who was behind that iconic Assassin’s Creed parkour video in Part 1.

When he eventually used one of the windows to enter a workshop, the celebration of craftsmanship took a very capitalist “product placement” turn. Sure, the work of the artisans was being showcased, but there were many closeups on the trademark logo of Louis Vuitton. How could that happen when sponsors are not meant to be on display within the opening ceremony show? The answer is simple: greed.

LVMH

A mere year before the opening ceremony, a different type of synchronicity happened. The IOC really needed money as the Paris Olympics were going over budget. Bernard Arnault, the richest man in France (and consistently in the top 5 in the world) decided he wanted his business empire to benefit from the games, so he suddenly dropped 150 million euros in sponsorship. Many people don’t know him or the logo LVMH very well, but more have heard of Louis Vuitton bags, Moet champagne or Hennessy Cognac. Arnault owns way more than these brands, including multiple media outlets. He owns Dior, ensuring that all the stars’ dresses would act as Dior ads. He owns the perfume chain Sephora, present both in the ads, but also as physical stops throughout the Olympic Torch Relay. He owns Chaumet, the jewelry company who designed the medals. And he owns Louis Vuitton, hence the LV cases being built in the workshop, revealed to the be on top of the Samaritaine department store… that he also owns. The reason there are hotel bellhops is this façade is the 5-star hotel Cheval Blanc… that he also owns. The craziest part is Bernard Arnault’s influence was not limited to the content of the show: he actually managed to extract the Samaritaine store from the infamous “grey zone” that I described in part 1. So while nearby small businesses were losing customers because no one wants to cross barriers and apply for a QR code with police to be allowed to shop, billionaire Bernard Arnault demanded that his store suffer no such fate. Everyone could just walk in the Samaritaine to make him richer, no questions asked.

Unionize

On the other end of the Synchronicité money spectrum were the dancers. The idea was to show people dancing everywhere in Paris, from the golden banks to zinc rooftops. This required multiple dance groups with very different work contracts. Big, official dance companies are often subsidized in France, so these dancers received their usual salary and diffusion rights to the tune of 1610 euros. But the independent dancers on the banks only made 200 to 300 euros for the performance itself (remember that number), and 40 to 60 euros in diffusion rights, with no reimbursement for logistics costs like travel to Paris. To protest against being paid a pittance compare to the other groups, during one of the on site rehearsals they stopped dancing and raised their fists instead.

They organized with a performers’ union and demanded better pay, warning to go on strike on the day of the ceremony: how French! Just 48 hours before the show, they partially won, and the production company raised their diffusion rights to 200 and 300 euros respectively. Unions and strikes may not make you rich, but they can definitely make your life better. Just as a reminder, a mere metro ticket is 4 euros during the game, and tickets to the ceremony sometimes cost above 1500 euros.

Medal Heist (La Casa de Metal)

Bernard Arnault’s Chaumet may have designed the medals, but they were actually made by the Monnaie de Paris, i.e. the French Mint. It is one of those Parisian Museums with a prime riverside location, but that very few people think of visiting. I go there for temporary events, which are sometimes quite original, like an immersive experience based on La Casa de Papel (Money Heist in English). So sure, there were the required Dali masks, red overalls and prop submachineguns, but they really used the location well, from grand salons to underground tunnels. The sequence in the foundry is probably the only shot with an actual artisan, so I’m glad they took the time to show the medal being made, complete with a discarded piece of the Eiffel shaped like a hexagon (the shape of France) surrounded by sun beams: Paris illuminates France, which illuminates the world. What can I say, bragging is very Parisian.

The 1980s are back

One cool thing about the dancing bellhops were their visuals, a mix between old working class references (like blue caps and red handkerchiefs tied around the neck at the turn of the 20th century), and the more recent working-class culture of early 1980’s hip-hop.

In 1984, hip-hop culture was introduced to many non-Parisian households thanks to a weekly show on the #1 TV channel in France: H.I.P.H.O.P. It was hosted by Patrick “Sidney” Duteil, the first Black host on French TV, who was inviting visiting artists like Afrika Bambaataa or Madonna, but also teaching French kids how to dance.

A key breaking practice spot in early 1980s Paris was already the very Trocadéro esplanade used by the Olympics, where the formal part of the opening ceremony took place, opposite the Eiffel Tower. Children would practice there if their parents let them, but most often at home, to enter H.I.P.H.O.P. ’s closing breaking battles in the hope of winning national fame and prizes. Sidney’s lessons focused mostly on popping and locking, but because of the white gloves (and sometimes hats for breakers), most people referred to the dance as “smurfing” or just “le smurf” in French. My original disclaimer still applies: I have no idea whether any of the above is what the creative team had in mind. And to be fair, another “Smurf”, appearing later in the ceremony, kind of stole the show.

The first fail

Synchronicité’s biggest failure is probably the IOC TV director’s lack of synchronicity with the artists. The amazing Guillaume Diop, danseur étoile of the Paris Opéra, gave an exquisite performance on the rooftop of the Hôtel de Ville, and the shot was meant to expand to reveal multiple other dancing groups on different rooftops.

I don’t know whether it was the rain preventing drone use or poor planning, but all we got was barely a glimpse at the Paris Fire Brigade (the only streams of water not actually in the Seine but on a bridge), and tiny pixels of dancers on other rooftops. Considering how difficult and dangerous it was to dance on these slanted and bent surfaces under the rain, it is normal several of these dance performances got cancelled, but it is a pity that the ones that did happen were not properly broadcast.

Get ready for liberty and love!

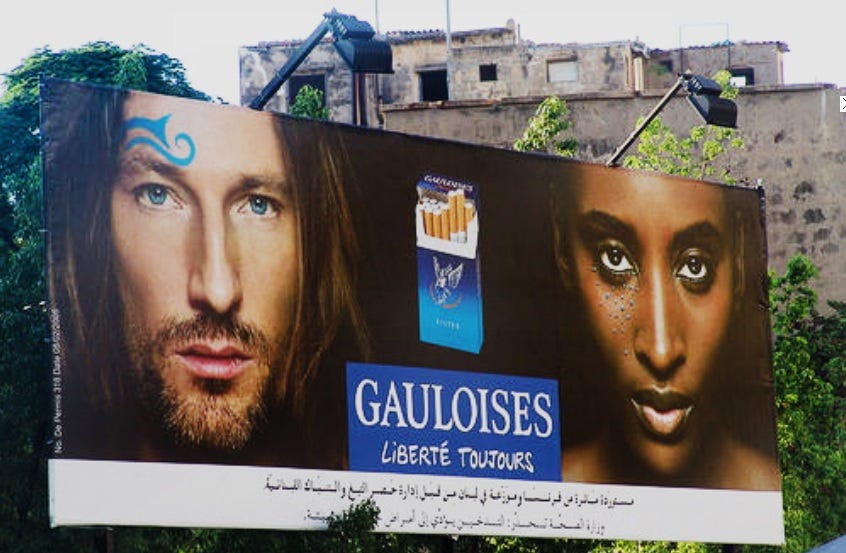

The young dancers ended as couples, forming a heart with their arms: people create love by being together. This also announced that the next act would probably have a lot of it. Furthermore, their common but diverse and subtle golden “war paint”, their different outfits but in a unified style, their youth and teamwork, reminded me of another 1980s reference: the Gauloises cigarette ads with their blue “war paint”. The iconic French brand’s slogan “Liberté, toujours” (Freedom, always - ironic for an addictive substance) was still used in Lebanon after cigarette ads were banned. And this, albeit in a very subliminal manner, also announced the next Liberté act to me.

Between Manpower, H.I.P.H.O.P., and the Gauloises tribes, the 1980s references that kept piling up finally connected in my brain: the aesthetics of this opening ceremony were inspired by Jean-Paul Goude’s 1989 bicentennial celebration of the French Revolution! Unapologetically bright colors, a party atmosphere, a parade down iconic locations (in 1989 it was the Champs Elysées towards the Place de la Concorde) —it was all there. It started to wonder, if I was correct, would they push the homage all the way, i.e. would there be a Black Marianne?

Best. Cameo. Ever.

Before we switch to “Liberté, toujours”, including love, I must unpack a short, but very successful aerial shot, which happens to be my favourite Easter egg of the entire ceremony.

We see a man perched on Notre-Dame’s spire, right under the gilded rooster. This is the new rooster (the old one couldn’t get restored), which contains relics of Saint Denis, the first bishop and patron saint of the church in Paris (remember his name for later), relics of Sainte Geneviève, patron saint of Paris, one of the 70 thorns of Christ’s crown, and a parchment inscribed with 2000 names of all those who, directly or indirectly helped rebuild the church. Some will see the man as the embodiment of the rooster, symbol of France and indicating which way the wind blows. As he’s wearing feathers, some will see it as a nod to Lady Gaga’s “Mon truc en plume” earlier. But as the bells of Notre-Dame started ringing, many will see him as Quasimodo, the Hunchback of Notre-Dame in Victor Hugo’s novel “Notre-Dame de Paris”, or one of its many adaptations, from Disney to a French stage musical.

But this actor/acrobat already played another hunchback wearing this very outfit, in one of his own plays: this is Thomas Jolly as the Duke of Gloucester in his rendition of Shakespeare’s Richard III… That’s right, Thomas Jolly, the very director of this opening ceremony!

You could see his proximity to the rooster as adding himself to that long list of names of people who helped rebuild the spire. After all, the rooster is a loud and proud animal. But it gets better. This cameo is also an homage to another Notre Dame cameo: architect Viollet-le-Duc’s self-representation among the apostles statues on that very spire! The spire itself was added by Viollet-le-Duc, one of the many over-the-top elements he added to make Notre Dame “more gothic, more medieval” by his own standards, hence the hordes of gargoyles, chimera etc. Viollet-le-Duc was criticized for going too far, for imposing too much of his style on an old respectable building. Thomas Jolly fully knew he would receive the same criticism. But there are a couple differences: Viollet-le-Duc represented himself a Saint Thomas, patron of the architects. But unlike the other apostles who are looking outwards and down at the people of Paris, Viollet-le-duc is looking inwards and up, back at his own spire, his own creation. He even wrote his name on the ruler he is carrying.

The less saintly Thomas, Thomas Jolly, climbed even higher than the Viollet-le-Duc-as-Thomas statue, and is literally hanging from the cross (he did that too, in Richard III). But he is looking outwards, at the city, because the entire city is his creation for one night!

Everyone can still enjoy this shot just as “Quasimodo with feathers”. But the added layers, both personal and proper historico-architectural references, make this scene pure genius - and oh so Parisian.

To be continued

If you enjoyed these explanations, please consider purchasing my audio walks here. I share all kinds of stories about unknown parts of Paris, and even if you’re not physically there you can listen to them at home, like a podcast: https://voicemap.me/publisher/comte-de-saint-germain

Thank you for such a detailed breakdown!

🙏 Loved watching this so much and felt enlivened by the spectacle and the complexity….Your analysis is fabulous. 🙏