"The whole ceremony was very *you*" Part 6: The End

Can you believe that, three months later, the Olympics Opening Ceremony is still making waves? So much that it triggered a parliamentary hearing? Time to wrap this up —with the most shocking bits.

This walkthrough is finally reaching the parts that everyone —and not just the French— talked about most: the global scandal, the sheer beauty, the tears, and the reasons for so many misunderstandings. This is the longest chapter, so please find a comfortable seat, and remember to stay hydrated.

Festivité

After going through Parisian clichés, unity, history, aspirational values, and a nod to sports, it was finally time to party! If you ran into stills (i.e. very specific angles and framing) of Festivité’s first swooping shot, I won’t blame you for seeing Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper reenacted by a very diverse crowd, including —but not limited to— famous French drag queens surrounding iconic DJ and lesbian activist Barbara Butch.

Apart from its artistic qualities, The Last Supper represents an event that is very important for many people, and at the same time completely fictional for even more people. Most of the world’s population isn’t Christian, but the largest colonial powers of the past two centuries —as well as the country currently exerting military and cultural domination over the rest of the world— have had large Christian populations and Christian rulers. France is often mistakenly presented as a Catholic nation by English-speaking media, but the majority of French people say they are not religious. This goes beyond neutrality and agnosticism: there are way more convinced atheists than practicing Catholics in France. That being said, Christianity is still the #1 religion of people who say they are religious, and it has had a major impact on French culture, including the arts, for nearly two millennia. From the dates of major school holidays (Pentecost, Christmas, and Easter with the serial numbers filed off) to that totally-not-religious Olympic mass attended by government officials, Christianity’s influence on French society cannot be ignored. But French people also get to make fun of it, as much as they want. The 1905 law separating church and state means the French are free to believe in any religion —or none— without repercussions from the state. In theory, the République doesn’t officially recognize, condone or subsidize any specific religion. In practice, it’s a bit more complicated, e.g. there a regional exceptions. But it would be illegal —and shocking— for a French president to swear an oath of office on the Bible. This would indicate favouritism of the Republic towards one religion, whereas the president is supposed to equally represent atheists, Buddhists, pagans etc. Blasphemy is perfectly legal, and even culturally encouraged for historical reasons (see below). This means you can advocate for spitting on saints and killing God, as long as you stick to targeting dogmas or beliefs, and you don’t threaten the believers’ actual safety. Threats against physical persons constitute crimes, threats against beings whose existence has not been proven constitute free speech.

People who live in more religious countries often wonder why France cares so much about making fun of religion. For centuries, in blatant contradiction with the teachings of the gospel, French church authorities have sided with the rich against the poor, the powerful against the weak, the elite against the people. From the 1871 Paris Commune to recent fights against marriage equality, or against a woman’s right to choose, church authorities have been at best very neutral towards oppressors, and at worst actively complicit with them. For a more recent example, when priests (some of whom did help the poor, like Abbé Pierre) proved to be sexual offenders, they were protected by the church authorities, against the law. For decades, the French Catholic church put its own reputation, and the comfort of its criminal priests, way above the safety of past, present and future rape victims. Formal pushback against religious power took the legal route 120 years ago, and nowadays expresses itself more through artistic creativity and humour. Left-wing practicing Christians do exist (see Timothée de Rauglaudre’s Les moissonneurs ) but they represent a minority, and are often very low ranking within the French Catholic church. And when famous bishops like Jacques Gaillot get a bit too progressive, they get side-lined until their death.

So what was the real problem with that fleeting nod to The Last Supper, which was extremely mild compared to any Charlie Hebdo cartoon? Said nod was, as astutely remarked by my partner, made by unapologetically queer people. As I wrote in Part 1 , the only real joke making fun of Christian dogma in the entire ceremony was right at the beginning: “Zizou Christ!”. But it was done by rich and famous straight men wearing gender-conforming outfits. They get to have fun with religion. How dare non-mainstream fat lesbians and bearded drag queens make a reference to the Bible in their segment?

As you saw in earlier posts, Festivité was not the first genderbending of the evening —by far. Enchanté already included a pink drag queen and a papier mâché caricature of Joan of Arc (yes, she cross-dressed), while Sororité unveiled a golden statue of scientist Jeanne Barret, who pretended to be man. But the former was only there for lighthearted fun, and the latter were long dead. God forbid living queer people dare make jokes about serious themes!

Dansons sur le pont / sous la pluie

Even without this cultural context, the visuals were clear: just as the camera had zoomed out to reveal that Liberté was not actually about Marie-Antoinette, but rather about the people of Paris fighting for a better life, Festivité was not about The Last Supper. The camera panned out and pivoted to reveal that the table was actually a catwalk, that there were people sitting on both sides, and that it was a fashion show, i.e. a very Parisian thing. In the French version of the broadcast that I screenshot to illustrate these posts, costume director Daphné Bürki named the designers, like in any fashion show, as well as the models.

There was absolutely no potential reference to any Christian imagery beyond the first shot. Even the French TV commentators couldn’t care less: they were too busy expressing amused shock that the playlist included such cheesy classics as Ottawan’s D.I.S.C.O. Bürki confirmed the songs were very purposefully chosen to turn Paris into the largest and most inclusive club in the world, featuring not just avant-garde electro bangers, but also all the big commercial dance hits played at regular weddings and countryside balls.

As Sportivité was probably cut short by the rain, parts of Festivité seemed to act a bit as filler at times. Models and dancers did multiple walkthroughs, and the action eventually shifted from fashion show to proper dance performances. Many styles were represented, from krump to ballroom to contemporary dance to traditional bourrée from Auvergne. This folk dance (and one outfit that included an Alsatian-inspired giant knot) were one of the very few nods to the province in the entire ceremony; again a reminder these were the Paris games, not the all-France games.

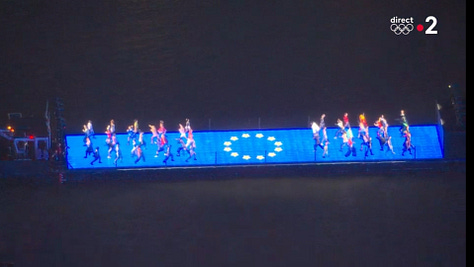

A final confirmation came with the dance troupe on the barge fitted with a led dancefloor. As Swedish band Europe’s The final countdown played, the European flag filled the barge’s screen and stars surrounded the Eiffel tower, echoing the fact that many Parisians would rather move to another large European city like Berlin or Barcelona than say, within France to Angers or Antibes. The European Union motto “United in diversity”, and the focus on Eurodance hits confirmed the “party for everyone” aspect of Festivité.

A good example was the huge hit Freed from desire by Gala, which topped the charts for months in the 1990s. It later came back as a football chant, and was reborn once again as an Olympic & Paralympic crowd favourite during the 2024 games.

I am no big fan of fashion, but I was impressed by the diversity of both outfits and bodies featured in this tableau: not everyone was traditionally symmetrical, skinny and white, but everyone got to shine. The rain did not stop the models and performers: Paralympic fencer Bebe Vio was beaming in the storm, and bearded drag queen Piche wasn’t scared to go down on all fours in the water. I since learned she is also a talented rapper and singer! The more acrobatic dancers were just epic: Bboy Haiper dropped his crutches to break, Germain Louvet pirouetted and progressed en pointe through the catwalk, both in actual puddles on the red carpet... Just incredible!

When the Torchbearer reappeared I was ecstatic: I had just recognized the third performer who was in Street Art at Grand Palais: Andrea Catozzi! A dancer and acrobat rather than a freerunner, he managed to land his trademark kicks and jumps in the cumbersome costume, on the wet floor… while holding the torch! The names of the other athletes who played the Torchbearer have since been publicly released, and I must admit I got the first one wrong. But a 75% success rate at unmasking acrobats only based on body language and location is still pretty good, right?

But wait, what about the naked blue man?

After a while, a giant silver platter appeared, revealing Philippe Katerine painted in blue, with orange facial hair, covered in grapes and flowers. The fact that people thought he was portraying Jesus befuddled me. When I first saw the blue skin and flowers, I wondered what Vishnu was doing here, and then I saw the grapes and was like “Oh, it’s Bacchus/Dionysus, god of wine, party, theatre, and excess!” Not only do most French parties come with alcohol, but wine is part and parcel of everyday French culture. The Paris wine museum is just a couple of bridges away from Passerelle Debilly, in the bourgeois cemetery that is the northwest of Paris. Dionysus’ presence is also a hidden reference to Paris itself, and to key Olympic sites. I already mentioned Saint Denis holding his head in Liberté, and his relic inside the Notre-Dame rooster. Guess what is Saint Denis’ name is in Latin? Dionysius. Dionysius, patron saint and bishop of Paris, Dionysus god of wine, and partying in Paris… get it? Furthermore, both Stade de France, the main Olympic stadium, and the Olympic village are located in the northern suburb of… Saint-Denis. And its inhabitants are called Dionysiennes and Dionysiens. Full circle. There is even another connection between Bacchus/Dionysus and the Seine, albeit made up, which I’ll explain later.

Philippe Katerine was probably unknown to most non-French viewers, but he is well recognized in France as a quirky singer and actor, mostly associated with being funny, sensitive or just weird —not a anticlerical firebrand at all. His most famous role is probably of a swimming pool attendant in Le grand bain, a sort of French The Full Monty about middle-aged men going through difficult times and finding themselves through synchronized swimming. While some scenes make Ken Loach-style political points, it’s overall a feel-good film about the power of sports and friendship. As such, it was projected during the Olympic and Paralympic games in various Parisian fanzones, bringing things full circle with the ceremony. Before appearing on stage, Katerine was best known for his 2005 hit Louxor j’adore, where he sings about loving to watch people from all walks of life dance in a night club, from its bar. A key gimmick in the song implies him turning off the music: “Je coupe le son!” When this is played at a French party, people stop dancing and loudly complain. So on the night of the ceremony, the lights even turned off in the barge, while the dancers pretended to complain. Then Katerine’s voice quickly announced turning the music back on with “Et je remets le son!”, to dancers cheering and resuming dancing. One final “Je coupe le son” later, Katerine himself made his grand entrance, singing his new song “Nu”. Its lyrics are about how being naked is intrinsically peaceful, how there would be fewer wars if we all remained naked from birth. So it’s really a funny and touching song, similar in message to Imagine, but with added Katerine humor & weirdness.

This message of nakedness and peace is actually very on brand for the Olympic games. It loops back to Greek athletes who would compete naked, and reminds people about the original Olympians: the gods of Olympus. Even the very specific stage layout and poses of the performers is inspired by a painting that, to be fair, I didn’t know before the ceremony: Jan van Biljert’s The Feast of the Gods (it’s missing a left panel, so several characters are missing).

Once you’ve seen it, you cannot unsee it, so here we go:

A: at the forefront lies Philippe Katerine as Dionysus/Bacchus, he props himself on one arm during the performance too. There is no Jesus lying down in The Last Supper.

B: center stage, behind the table, is DJ Barbara Butch as Apollo, the cerebral god of beauty and fancy arts (as opposed to Dionysus, the filthy party god). She played turntables instead of a lyra, but there is also a glittery pink lyra right next to her for those that didn’t get it. How many lyras can you see in The Last Supper? Unlike the other gods, both van Biljert’s and the ceremony’s Apollo have a halo, because Apollo is also Phoebus, the sun god.

C: Flora, goddess of spring, is striking a very clear pose in the background, though the pose is also reminiscent of the dancing satyr. At some point, while Katerine is falsettoing “Nuuuuu!”, everyone around him does this same dancing satyr arm movement. Remember, a painting can only be a snapshot, but the TV scene was full of movement, the entire time, and mostly made of dancing, partying people moving across the table stage like the painting satyr is doing. Satyrs are sexual party creatures… and so were the performers. There are no sexy dancing apostles in The Last Supper.

D: the armored Athena/Minerva and Ares/Mars are played by Nicky Doll, repurposing her existing Joan of Arc stage costume here. You could even argue Doll is the fusion of the armored characters and the female characters showing skin here, including Venus.

E: the presence of a child on the catwalk is no coincidence, as the god Eros/Cupid was at the table in the Feast of the gods, supported by his mother Aphrodites/Venus. Cupid is played by a 11 year-old krump dancer, Québecoise Adeline Kerry Cruz, supported by her mentor JR maddrip. Again, how many children can you see in The Last Supper?

From catwalk to Katerine, this entire sequence is much longer than the fleeting nod to Da Vinci’s painting, and the true meaning of the scene is clear: the gods of Olympus have descended upon Earth, they are feasting in Paris, and we should all have stayed in our birthday suits.

Even though Katerine was not actually naked, but wearing a loincloth and covered in glittery bodypaint, this sequence was censored on TV in countries where religion has a strong influence over media, like Morocco and the USA. In China, the commentators were just confused and remained silent, so people on social media kept asking what this all meant. In the end, the Chinese audience consensus was to find Katerine cute, so much that they created everything from fan art to desserts, shaped and dyed like “The smurf artist”. Honestly, Papa Smurf (le Grand Schroumpf in French) is just as valid an interpretation as anything related to Jesus. Katerine ended this sequence with his trademark “et je remets le son!” as if saying “OK, I’ve done my own thing, now you guys try to go back to normal —if you can”.

Obscurité

The dancing barge, which had been displaying the same Versailles marble court pattern as during Rim’K’s performance, had a “the floor is lava” moment. Dancers dropped like flies to represent the consequences of man-made climate change, which, ironically, was made worse by the Olympics, and was responsible for the insane amount of rain we got in Paris that night and throughout that summer. The obligatory Imagine cover was a rather standard rendition, but maintained the “our world is on fire” theme, with Sofiane Pamart’s flaming piano unintendedly mirroring the earlier drenched piano. The fire could also be understood as a message about global warming, but the call for peace was a clear reminder that one of the countries was still carpet bombing the children of another one while claiming self-defense.

I was glad to see Juliette Armanet singing it, because she had been trashed by French conservatives for weeks for having dared to criticize Les lacs du Connemara, the most famous earworm by Right-wing singer Michel Sardou. I used said earworm for a tongue-in-cheek and drenched short video, because the lyrics describe lakes and scorched earth. Like the ceremony, the short video ends with the Eiffel Tower.

Note that Michel Sardou was not invited to perform: the artistic, political and generational vision of the creative team was clear.

Solidarité

A pre-recorded video then showed a hooded figure dressed in very shiny silver or chrome, donning the Olympic flag as a cape. She re-appeared live, on a fantastic mechanical horse galloping down the Seine to some scary and/or epic music, while black & white images of old Olympiads cycled on TV. It was not Death, as Death would not be carrying a flag but a scythe. It was not any other Rider of the Apocalypse, because by now it should be clear that this ceremony is not about the Bible. If anything, it’s a person averting the apocalypse that was just portrayed Obscurité, thanks to the Olympics.

The rider was not Joan of Arc either: her trademark bowl cut and armor had already appeared previously in Enchanté as a caricature, and was ironically alluded to by drag queen Nicky Doll’s outfit in Festivité. Jeanne d’Arc, just like Napoléon, de Gaulle and other conservative, warlike icons, was never the main focus of this ceremony. I cannot stress enough how much Jeanne d’Arc is a symbol of nationalism and xenophobia for the current French Far-right, because of her “mission” to convince the French king to kick the English out of France. Countless fascist rallies have been held around her golden statue near the Louvre, so she is the opposite of a symbol of international peace and unity.

Jeanne is also a symbol of religious fervour or fundamentalism. In secular France, we don’t say she heard the voice of God or Saints: we say she just “heard voices”. The statue depicting her in the Louvre literally refers to these voices as “her voices”. In recent years, people have tried to spin a “strong independent woman who defied norms and was killed by powerful men as a result” feminist angle. But we have much better role models for this: none of the golden women in Sororité advocated for the slaughtering of foreigners because voices told them to.

To be fair, costume designer Jeanne Friot did refer to the rider as “her Joan of Arc” on Instagram, because the outfit (including armor by Robert Mercier) was indeed partly inspired by representations of the Maiden of Orléans. She even went “full shiny & chrome”, just like Niky Doll’s outfit, instead of the less reflective look of natural steel. But director Thomas Jolly was very clear: the rider was the Celtic goddess of the Seine, Sequana, and/or the Olympic spirit. When in doubt, always ask the director and writers rather than the stylist or the lead actor. In 1959, Charlton Heston never thought he was playing a gay love scene when his character Ben Hur reunited with his “old friend” Messala —but he was.

Sequana

Bringing the flag all the way across Paris to the site of the formal ceremony took quite a long time, which probably felt too long for TV audiences. But long scenes with tense music and harsh white lights are a signature style of Thomas Jolly’s stage work. Furthermore, the rider was one of the very few live performances that all seated ticketholders got to see. Most of their night was spent under the rain, watching giant screens and athletes’ boats. Even people who were seated right opposite the Eiffel tower —some of whom dropped 2000 euros for front row seats— didn’t even see the laser show, as the projectors only pointed the other way. I like that Sequana made such an impression, because she was indeed a big deal for us Celts. People would travel to her temple, located near one of the river’s sources (way closer to Dijon than to Paris) to ask for healing and other wishes. They would leave little models of body parts as ex-voto and hundreds of those have been recovered. But unlike what was explained by the creative team, Sequana was never the daughter of Bacchus / Dionysus: we had our own gods, independently of the Greeks, and way before the Romans invaded. The “daughter of Bacchus” concept comes from one of many “nymphs of the Seine” stories written much later, by French 17th and 18th centuries authors. These are disconnected from any religious basis, were written centuries after Christianity had replaced paganism in France, by people who didn’t even know who Sequana was, because her temple was long buried by that time and had yet to be rediscovered. But the the internet happened, and people conflated the actual, archeologically documented Celtic goddess with the made-up literary nymphs. The ceremony’s creative team decided to go with this internet fusion and I’ll gladly grant them that artistic license: unlike certain monotheist fanatics, I won’t ask for anyone to apologize or die for a show.

As Sequana kept passing bridges, wings would light up behind her, symbolizing the release of peace doves (real doves aren’t used anymore since an unfortunate impromptu Korean barbecue). The rider was billed as Floriane Issert, a gendarme, but on the boat it was a different woman: Morgane Suquart, the co-creator, engineer and test pilot of the boat that supported the mechanical horse. I originally thought the specially designed, low profile trimaran was a submarine, with an unseen or remote pilot, but it was an actual boat! The best part is Suquart actually steered the boat using actual reins that moved the rudder, in real time. She only had an earpiece to help with navigation between the stone pillars of the many bridges, in the rainy night. I later went to see the horse up close, and it’s a thing of beauty. Sequana’s outfit was also on display, and I was surprised that some of the straps on her costume were actually printed on a bodysuit. On TV you couldn’t tell, and apparently it’s both part of the designer’s style, and a common technique to make costumes both cheaper and more comfortable for the performers.

Solennité

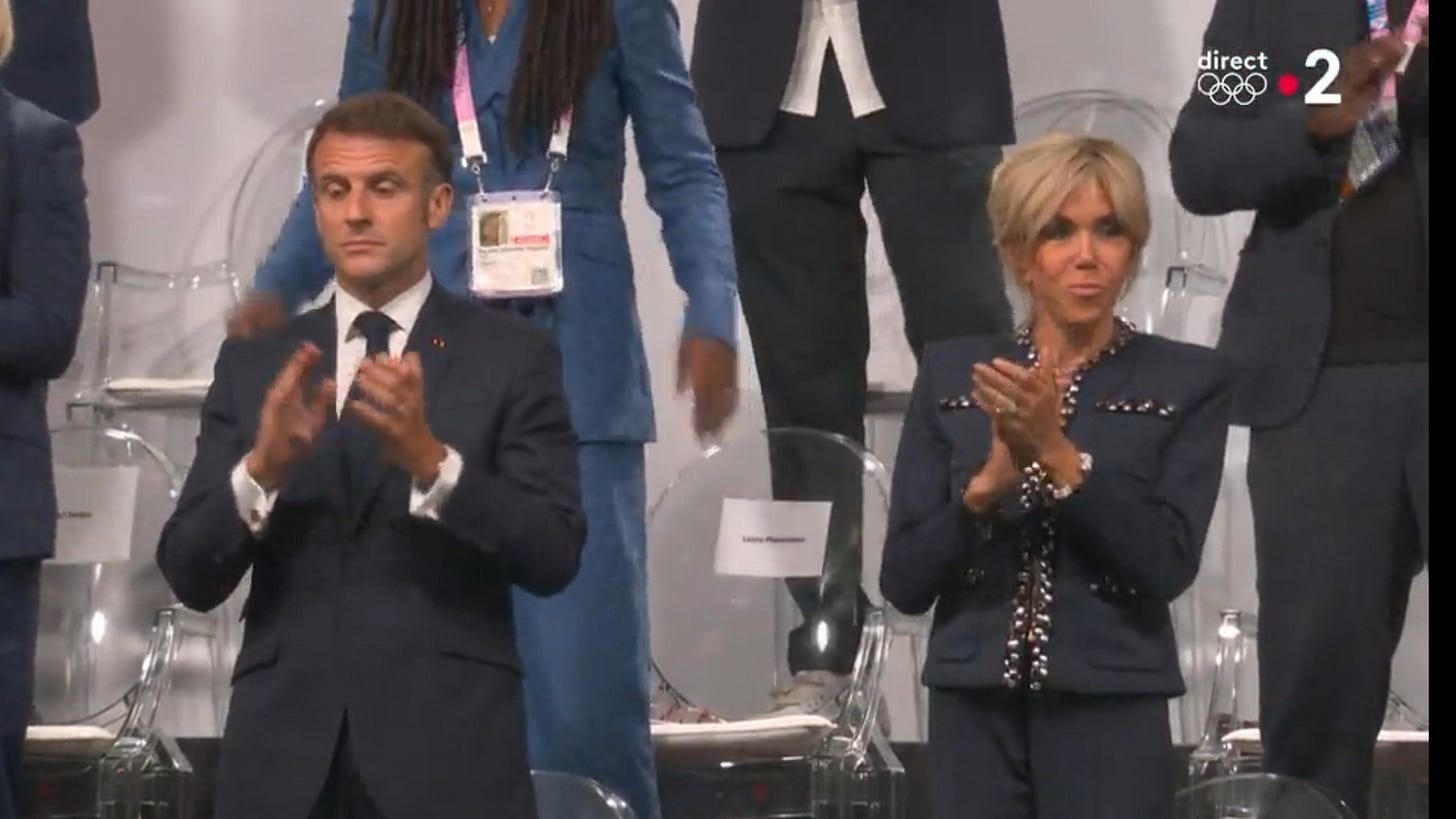

I found the “official protocol” part of the ceremony very military and boring, nothing new here. Silver lining: various recordings confirmed that Macron was copiously booed (way more than in the IOC TV sound mix), which he totally deserves. He had already been booed during the Rugby World Cup, and his ongoing war on the poor and on democratic values caused him to be booed in all the other ceremonies, including the final Paralympics Closing Ceremony. So he decided to create a fifth ceremony, first to get more personal glory out of the games (he did try to insert himself wherever he could during the events), but without ever risking standing alone in front of a crowd again. In that taxpayer-paid, French-only fifth ceremony set at the Arc de Triomphe, he always surrounded himself with as many athletes as possible, so that booing him would have meant booing the beloved athletes too.

As I was bored by the show on the screen, I observed people around me in the bar where I had retreated, and one man really liked Solennité. He kept going “wow!”, asking his neighbours to admit this was a proper display of French grandeur: the flags, the horses, the soldiers, the lasers on the Eiffel Tower. He was one of the very few off-duty police officers in Paris that night, and this was clearly the moment of the ceremony that was designed for people like him. Many commentators forgot Solennité because of Festivité’s strong visuals. But if you were into patriotism and uniforms, you were covered too. Everyone was welcome. What’s quite funny is the most serious and disciplined participants of the night were the ones who blundered: they hoisted the Olympic flag upside down. I honestly don’t care, mistakes happen. But drag queens danced in heels under the rain, on a catwalk full of puddles, without falling —just saying.

Sign singing in the rain

Victor Le Masne’s decision to cover Cerrone’s 1977 Supernature for the Eiffel tower laser show was another one of those “nod to the older generations, while adding new elements” moments. From the 1970s to the 1990s, any French laser show just had to be to set either to this very track… or to anything by Jean-Michel Jarre. Both musicians showed up in person for subsequent ceremonies, again coming full circle.

The new staging element was Shaheem Sanchez’ sign singing and dancing to Supernature, alone, above an audience of partying athletes, under the rain, in front of an impressive light show. The choice of this performer triggered a controversy within the French Deaf community, as he used American, and not French Sign Language (Langue des Signes Française, LSF). Some argued that, as Lady Gaga sang in French, he should have sign sung in LSF. Others argued they should have showcased a French sign singer (there was one next to the stage, sign singing in LSF). Others noted that the original French-composed song was sung in English anyway, so you couldn’t hold it against Sanchez to sign in ASL. As a non-Deaf person, I am not qualified to answer, and I was just happy that chansigne was featured. That’s right: chanson + signe: chansigne.

Éternité

After many more champions, from global Olympic glories to French athletes who became politicians to current Paralympic athletes, I was getting a bit impatient as we had already seen dozens of Olympic torch relays for weeks before the Opening ceremony. But I was moved by the image of 100-year old former cyclist Charles Coste, the oldest living gold medalist, now in a wheelchair, transmitting the flame to former sprinter Marie-José Pérec and current judoka Teddy Riner. Again a very strong image mixing the old and the new: wrinkly old white France was passing the torch to younger Black France to finish the job. Now, to be fair, Marie-José Perec is 56 and long retired, and at 34 year-old Teddy Riner is closer to the end of his impressive career than the beginning, so they’re not exactly youngsters. And even at the national level, people from Guadeloupe have been French for longer than people from Nice, and there have been Black French people in France for centuries, even on the mainland. But the visual strength of the symbol still moved me.

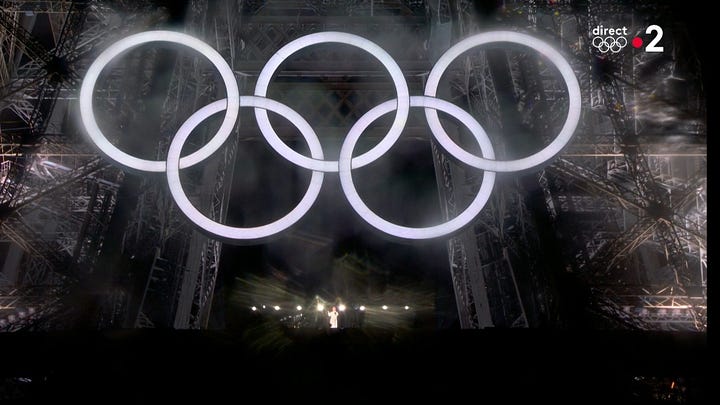

The cauldron itself was again a mix of the old and the new: a captive helium balloon as had happened on that very spot centuries ago… but filled with advanced technology to make everyone believe it was actually fire, as an additional nod to the hot air balloon, the French montgolfière featured earlier in the animated sequence. I already liked the torch’s design, featuring the water of the Seine, the air above it, ending in a fire to produce light. So I loved that the cauldron was misting water with air and electric light to give the impression of fire.

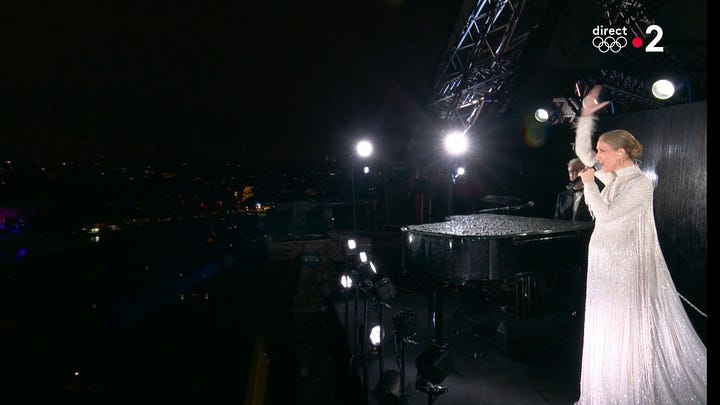

The cauldron made the Seine and the City of Light become one once again, by rising through the air in the night sky, under the rain, for yet another impromptu marriage of the elements. French people immediately recognized the melody of Edith Piaf’s and Marguerite Monnot’s L’hymne à l’amour (Anthem to love) which contains a lot of sky- and love-related metaphors. Piaf originally wrote this song about the intensity of her love for boxer Marcel Cerdan. The lyrics talk about how the sky could very well falling on lovers (an ancient Celtic fear, but also an image of rain), about them not giving a damn about the rest of the world (just like in Aya Nakamura’s cover of Aznavour’s Formidable) and about lovers being freed from their problems by rising to the heavens. The following month after Piaf’s first public performance of L’hymne à l’amour, Cerdan died in a plane crash. She kept singing the song throughout her career, and dedicated it to him. Céline Dion singing it on the Eiffel Tower, took this story and the song’s lyrics even further. She had last sung this very song at the American Music Awards in 2015, to honor the victims of the Paris terrorist attacks that had occurred a few days earlier, with images of the Eiffel tower in the background:

And now there she was, nearly 10 years later, on said Eiffel tower, honoring the City of Light. Dion’s personal history of illness and of losing her partner resonated on so many levels with Edith Piaf’s that people around the world —myself included— just burst in tears. The song even resonated with costume director and commentator Daphné Bürki’s own lived experience: she dedicated the show to her partner who had died just a few months earlier, while she was working on this very ceremony.

The IOC-imposed TV director chose to mostly show close shots of Dion, but the Eiffel Tower light show was uniquely crafted to accompany the song’s structure:

While we were in tears, the organizers wanted to make it clear that yes, this entire ceremony was about unity and love.

They displayed final a title that slightly edited the original song lyric “Dieu réunit ceux qui s’aiment” (God reunites those who love each other), into to “Réunir celles et ceux qui s’aiment” (“To reunite those who love each other”). This edit removed the reference to God, in a classic French laïcité tightrope exercise. The original lyrics that mentioned God were indeed kept in the song: religion was not erased from Céline Dion’s performance. But the subsequent, government-funded title shown on public TV did not use religious words. The rewording also used gender-inclusive writing. In French “ceux” is masculine, while “celles et ceux” specifically includes both women and men. Macron had made it very clear, on camera, that he and his beloved Académie Française considered that the masculine “ceux” also worked as a neutral word, i.e. also included women, i.e. including “celles” was superfluous. The creative team behind the ceremony clearly disagreed with this grammatically correct but sexist rule, so spelled out “celles”. The sentence was still grammatically correct, it didn’t use any strange hyphenation, so conservatives couldn’t complain, but the message was very clear.

The morning after

Including online replays, the Paris 2024 Olympics opening ceremony is now officially the most watched programme in the history of French television. Audience reactions were overwhelmingly positive, with 86% of French people polled declaring the ceremony “a success”, half of whom “a great success”. An excellent summary of the average Frenchman’s reaction comes from

’s Reel below.On that night, many French men were caught on camera doing the exact same “deep exhalation, followed by tears you try to stop by exhaling some more, but just can’t” on the banks of the river, at home and in bars.

So, who was the minority who thought it was a failure? Mostly people on the more racist, monarchist, homophobic, religiously bigoted and generally Far-right end of the political spectrum. In France, these haters had already complained live during the ceremony on Twitter. In the US, it took a bit longer due to the time difference. But the Americans who complained the loudest were of a similar ilk. Rich individuals with major media access and a Far-right following, e.g. Elon Musk and Donald Trump. But also, conservative religious leaders and fundamentalist practitioners of various monotheist religions. In France, the loudest complaints came from 24h news network pundits, who are paid by French Far-right billionaires like Bolloré. Again, the vast majority of French people recognized themselves in the ceremony: old French people got their Eiffel Tower, their accordion and their cancan, queer people got their trouples and their drag queens, law enforcement got their uniforms, their flags and their fighter jets… Even musically it was all there: metal, hip-hop, baroque, disco, 60s to 2020s pop, military music, Edith Piaf, EDM, techno, you name it. This is what inclusion means: not just a ceremony for rich Right-wing boomers, but a ceremony for all Parisians. Or rather for those Parisians that haven’t yet been forced to leave their beloved of the city for the heinous crime of being poor.

But there was also some criticism from the Left, as French progressives tweeted during the ceremony things like: “This country looks really nice and inclusive, where is it? I would love to live there” “This is what France would actually be if the NFP Left coalition had won absolute majority” (the Left coalition did win an absolute majority… but inside Paris, not in the rest of France). Sociologist Fania Noël also wrote a brilliant essay on the danger of minorities wanting to be included in something that is also a colonialist, Islamophobic, sexist surveillance state. Did one evening of representation erase centuries of racial profiling, police brutality and systemic racism?

People also rightly commented that several people from Guadeloupe were cast in glorious, iconic roles… but France still refused to ensure everyone in Guadeloupe had access to clean drinking water. France chose to spend 1.4 billion euros on infrastructure to clean up the Seine in Paris for a few foreign swimmers, instead of spending a tiny fraction of that cost on the infrastructure needed to provide French citizens with a basic human right.

A positive effect of the diverse representation in the ceremony is that many inhabitants of Greater Paris, especially young people of colour, eventually decided to brave the outrageously increased transport prices to attend free Olympic events or just watch them from fan zones in the city center. Some explained their change of heart was due to watching the ceremony: “Wait, I am actually included in this! These games are for me too. It’s not just for rich foreigners who can afford the tickets.”

So what?

You may wonder why, nearly three months after the ceremony, I am still spending hours writing walls of text about its potential meaning. A fair question, with multiple answers.

I need closure

I posted Part 1 four days after the ceremony, and it’s high time I finished this series. But why did I start it in the first place? In theory, I shouldn’t attempt to dissect a piece of performing art: I am neither an artist nor a professional art critic, historian or sociologist. If art is meant to be such a private, subjective, personal experience, why am very publicly adding my €0.02?

Hatred

Opening Ceremony haters didn’t stop at the usual “what a terrible show”, “this is the end of French civilization” or “a waste of taxpayer money”. They bombarded the creative team and the performers with insults and hate speech. They repeatedly and very precisely threatened them, both in public and private messages, with assault, rape and murder. DJ Barbara Butch received fatphobic, sexist, homophobic and anti-semitic insults. Drag queen Niki Doll was called a pedophile by a UK personality with a large following. Artistic director Thomas Jolly received so many specific, violent threats, that he was put under police protection and had to give interviews accompanied with a bodyguard—while the games where still going on, and while he still had three ceremonies to deliver. Hate speech and threats are not free speech in France: they are illegal. People were willing to break the law because they felt attacked by the way a work of art celebrated culture, love and inclusion. Several artists pressed charges, and the French national police cybercrime unit is still investigating these thousands of messages.

Ignorance

The above hate comes not just from fundamentalism, but from ignorance and misinterpretations. As a former colonial empire, and still possessing quite a bit of cultural capital, the French tend to think their culture is universal. Part of it is genuinely believing their own national values would make the world a better place, part of it is refusing to accept they’ve been superseded by English-speakers. Some Parisians really think that French history and arts are so universal that they assume everybody knows about the Conciergerie, and everyone has seen Jules & Jim. Some French artists think their own work is so universal that it touches the human condition at its core, and therefore needs no explanations. People around the world will “just get it”. Was the ceremony’s team creative guilty of any of the above?

Or was secrecy so sacred, down to giving a fake ceremony title to French media, that the creative team consciously refused to divulge anything, and preferred to risk vacant, misleading or plain wrong commentary from worldwide journalists?

Scandal

In her

, French author and guide , who was travelling in the US at the time, asked herself these questions too. She did some digging, and dropped a major bomb: the press was actually provided with a very detailed media guide.As often with French cultural leaflets, or signs in museums, the guide’s English translation wasn’t great. So the 40ish-page pdf was not a very smooth read, but it did get the job done. It opened with very clear explanations, including a full page vision statement from Thomas Jolly, making it very clear that the ceremony intended to be progressive, diverse and inclusive, and not a martial or nationalistic celebration. The guide described what would happen during the ceremony, with a full minute-by-minute breakdown of the various tableaux, including when would be a good time to comment and when to stay silent. So surprise was not an excuse: the media knew very well what was coming. The end credits were so detailed that the guide even gave the names of the torchbearers, so presenters didn’t need parkour nerds like me to try and guess who was who.

But more importantly, the media guide also provided the historical and cultural context for the various tableaux. There is no mention of any Last Supper in Festivité, or of Katerine being either Jesus, Satan or Papa Smurf: the guide explains he is portraying Bacchus/Dionysus, and why. Nowhere does it say that the silver rider was Joan of Arc, or Death, but the Solidarité chapter does confirm it’s Sequana or the Olympic spirit. The fact that the BBC commentators did give the name of the silver rider on the live horse (they couldn’t know about the switch of the mechanical one) means they had indeed read the pdf. So why did they remain confused about the rest? When I saw this document, I was happy to see I had clocked most of the references, and that my long, rambling posts had not been in vain either. For example, the media guide did not cover important and recent political context like the racist attacks against Aya Nakamura, or go into any depth about Rim’K lyrical references to Michel Berger. So if you invested some time to read these posts, you did get exclusive content.

We’re not letting go

Non-disclosure agreements signed by the artists expired after the Paralympics Closing Ceremony. So revelations and behind-the-scenes photos are still fueling debates and analyses about the ceremony. Three weeks ago, the newly elected French Assemblée Nationale called a parliamentary hearing about the ceremonies, where artistic director Thomas Jolly was accompanied with historian and ceremony co-writer Patrick Boucheron.

They got to repeat their vision for the ceremony, and answered the MPs’ questions. Just like the post ceremony poll, 9 out of 10 MPs congratulated them and thanked, sometimes in downright fanboyish tones. And just like on Twitter, only the Far-right complained. A Rassemblement National MP even demanded to know why the TV director who covered the ceremony was English, and not a French citizen. It had clearly been explained, several times, on national TV, that the guy was imposed by IOC: this mix of xenophobia and ignorance is so typical of the Far-right.

During this parliamentary hearing, Thomas Jolly mentioned that the media guide found by

had been sent three days in advance to media. So not only did journalists have ample time to do their homework, but they also had all the elements needed for some quick damage control once the flame wars started. But I guess fueling online outrage triggers more engagement and captive eyeballs than the cold, hard facts.Even more recently, Far-right Catholics blocked the Passerelle Debilly by kneeling down to pray to “repair” what they considered to be “blasphemy” in Festivité . Funny how the French Right-wing, who is so quick to rant about the illegality of street prayers when it’s Muslims doing it, is suddenly fine with it when it’s Christians doing it. So much for the universality of France’s secularism.

Rebranding Paris

As you can see, this ceremony is still influencing the Spirit of Paris, its collective unconscious, its global image. People who have watched it will never look at certain monuments in the same way. Older people, whose image of Paris may have stopped at Enchanté, got a serious update. Younger people, who may have discovered the city by watching Emily in Paris, got a serious reality check: for example, Parisians of North African descent exist!

Whether people had clichés or already knew “real Paris”, this ceremony was also the first positive, global news item about the city in a long time. Last time Paris was showcased by so many news outlets at the same time was in 2019, the Notre-Dame fire. And the time before that was in 2015, the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan terrorist attacks. It was good to see Paris make such a global impact, in one single night, but this time for a celebration.

At the national level, the French had just gone through political hell due to Macron’s scorched earth approach to staying in power. The situation was so dire it caused me to start this Substack. After weeks of dealing with the fact that such a large percentage of their neighbours were full-on racists, or at least open to the idea of fascism, many French people were happy to take a breather, and to come together for a few hours.

During that one night, Parisians themselves reclaimed their narrative. Ici, c’est Paris. This is Paris: were here, we’re queer, and straight, and old and young, and fat and skinny, and disabled or not, and white and Black and Asian and North-African, and any combination thereof. We keep re-electing center-left mayors who try to promote inclusive values. They sometimes fail and sometimes succeed, in sometimes rather cringe, and sometimes rather glorious ways. We know Macron is the president of the old, the rich and the countryside, and that within Paris he is only loved by a bourgeois minority hunkering in the western arrondissements and posh suburbs. We hate Le Pen, and neither the father nor the daughter ever managed to get a strong foothold here. We live with all kinds of people, literally on top of each other, in the most densely packed capital in Europe, and we know foreigners are not the enemy.

I still believe this ceremony could have done without bussing the poorest of the poor out of Paris, and without turning the city center into a police state no-man’s land for maximum IOC profits. Macron could have kept more of the Seine’s upper banks open to the public as originally planned, allowing 600’000 spectators as originally announced, with more free tickets, and keeping the bouquinistes open until showtime. The nationally-imposed right-wing logistics that surrounded such a clearly left-wing work of art is still causing major cognitive dissonance for many of us.

The opening ceremony was very me

Like my audio walks, the ceremony covered major historical events, but made fun of clichés and referenced lesser known personalities. Like my Instagram feed, the ceremony had the catacombs, a masked dude on rooftops, urbex, artisans, meaningful depictions of historical violence, love, hip-hop, nonsensical humor, sheer badassery, playful use of public space and niche artistic references. It showcased people who are underrepresented in positions of power, underrepresented in French media, and underrepresented when international media cover Paris: women, people of color, the LGBTQIA+ community, people with disabilities etc. And just like this series of Substack posts, the ceremony was probably too long, belaboring certain points, going on tangents, at times navel-gazing and self-promoting. How meta is it to come full circle, like an Olympic ring —or a flying cauldron?

But the reactions, to both the ceremonies and to these posts, confirmed that what I write about Paris can be useful. Major media outlets don’t always bother to Read The Fucking Manual, or don’t give certain complex topics the depth of treatment they require. I do. Whether people sit down reading these posts for hours in front of a screen, or let my voice take them on a walking tours of the less-travelled parts of the city, I’m here for this. Thanks for being here too, and I hope you can, very soon, walk Paris.

Bonjour Comte. How fun to type this. Please excuse the familiarity.

Kudos for a well-informed, thoughtful, detailed analysis of the Opening Ceremony, the controversy it spawned in some circles, its meaning, far reaching implications and aftermath.

I've enthusiastically "restacked" the last installment in the series you shared here and hope many people get to read it. Well done.

PS: Thank you for mentioning my stories on the same topic.

Amazing piece, again. Thank you for digging so deep. I agree with you that Festivité got so much wrath because LGBTQ+ people were so visibly featured in it. As you note, while France has a long history of anti-clericalism and of mocking the church (for good reasons, I may add), anti-LGBTQ+ hatred is going strong and stronger.

As you may have heard, 7 people were recently arrested for their threats against Thomas Jolly. Their trial will be early next year, with hopefully more people joining them in jail. For one, I'm happy to see the police taking this seriously (although I have no delusion that it's because it has been such a high profile case). I hope it deters people who feel they can say whatever they want online, falsely secure behind their computer screen.